Hemingway Was Right (and ChatGPT Can Help)

NEW VIDEO

Hemingway Was Right (and ChatGPT Can Help)

Watch 25 minutes of my ChatGPT course FOR FREE

TRANSCRIPT

Hi everybody and welcome back to the wonderful world of Everything is a Remix. I'm gonna try some new things. I'm experimenting. I don't know what I'm doing or where this is going.

I know I told some of you I'm retiring from video, I stopped the kinds of videos I was making. It's a new game for me, this is a new chapter. I'm going to be doing things in a way.

I want to tell you about an exciting new project I have and share one of the best parts of it right here.

I have a new course about ChatGPT and AI. You can watch the entire first module, which is 7 videos, over 25 minutes of content, for FREE. There's a link in the description.

AI is the next frontier in creativity. And the best tool there is... is ChatGPT.

What for? For writing and for writing content.

ChatGPT helps you deal with this.

The blank page. The void. The abyss. That relentless blinking cursor.

You can get spooked here. When you're starting from nothing, it's easy to get overwhelmed with choices or overthink or procrastinate.

Remember what I'm about to say. Make a note. Screencap.

Rewriting is easier than writing. I'll say it again: rewriting is easier than writing.

ChatGPT gives you something to work with. It's not good necessarily, it's just... something. It's a start.

Some of you might be thinking: doesn't your first draft need to be kinda like... good?

No no no. No, it really doesn't. Common misconception.

Don't believe me?

How about the author Jane Smiley? She won the Pulitzer Prize. She said.

"Every first draft is perfect because all the first draft has to do is exist."

How about Anne Lamott? She wrote a famous book about writing called Bird by Bird.

"Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere."

Or most famously, Earnest Hemingway might have said "The first draft of anything is s--t."

We're not totally quite sure he said exactly that.

The first draft is often bad. Just like the first demo of a song is bad or the alpha version of your software is bad or the first prototype of your product is bad.

Thinking that the first draft has to be good will paralyze you. It'll stop you from starting.

ChatGPT can get you that crappy first draft, it can give you the raw material. Then you have to rewrite it pretty much completely. There won't be much ChatGPT left in it when you're done.

Sound like a lot of work? It's way less work than writing your own first draft and then making that better.

I'll say it again, rewriting is easier than writing.

When there is something there on the page, you can improve it and fix it.

And sure, sometimes ChatGPT will strike out. No matter what you do, its first draft will be a dud, you won't be able to use it. Was that a waste of time?

No, you still come out ahead. Because seeing what you don't want can shed light on what you do want. It's helped you narrow down the possibilities.

In sports, there's the expression "You're either winning or you're learning." Same applies here. Even when you lose with an attempt at a first draft, you learn, and you get closer to a solution.

How Remixing Grew Into a Multi-billion $ IP

How does creativity happen?

Step 1

We start with copying. Watch Everything is a Remix Part 1 to learn more.

Step 2

We take what we copied and we transform it. We stretch it, squish it, flip it, distort it, recolor it, add effects, or anything else you can imagine.

By the way, this includes making mistakes. You try to do one thing and get something else. Always take a moment to evaluate your mistakes. Mistakes can be free ideas.

Transformation is time-consuming tinkering. We make small revisions again and again and again, and over time, these turn your source material into something unrecognizable. The Daft Punk sequence from Everything is a Remix Part 1 is a fun example.

George Lucas was the first major entertainer to work in a clearly remix-y style. He took bits from other films and transformed them. This style is strongest in the original Star Wars from 1977.

Lucas initially conceived of Star Wars as a version of the Flash Gordon shorts from the 1930s. Overall, Star Wars still bears many similarities, which is why many science fiction fans think Star Wars is not science fiction. Flash Gordon was more of a fantasy. It was castles, princesses, and evil kings, much like Star Wars.

The style and swordplay of the Jedis are drawn from samurai films, like those of Akira Kurosawa.

Some scenes in Star Wars resemble those from famous Westerns, like The Searchers.

The template for the final Death Star mission was a variety of World War II films, like The Dambusters.

All these are just the beginning. Watch this sequence from the original Everything is a Remix series to see more. And for the deepest of deep dives, check out Michael Heilemann’s site, Kitbashed.

But transformation isn’t just about art and entertainment. It applies to innovation and business as well. That’s where we’re headed in our next installment.

BIAS: One of my most important creative tools

I want to share one of my most essential tools. It’s a four-step method for generating ideas called BIAS. That stands for Bound, Immerse, Arrange, and Stop. I’ll briefly explain each, but check out my digital toolkit, Get Ideas Now, for a more thorough explanation of this process.

How BIAS Works

BOUND

Start by defining the boundaries for your exploration. Creativity thrives within constraints. Pick a niche, like, for instance, early first-person shooters.IMMERSE

Next, immerse yourself deeply in your chosen area. Research and absorb knowledge through reading, talking to experts, and experiencing relevant products and culture.ARRANGE

Arrange your findings into narratives, maps, and connections. Push yourself to go deep—but beware of lapsing into analysis paralysis.STOP

Now, the twist: stop working! Go for a walk, take a drive, or just relax. After you stop working, your subconscious will work its magic. Ideas often arise in these quiet moments, so be prepared to capture them in your phone or a notebook.

Following these steps sets the stage for your subconscious mind to generate ideas. You might not be aware of the process, but it's happening beneath the surface.

In other words, getting ideas is just a matter of:

Picking a specific topic

Uploading a bunch of information to your brain

Reviewing it and arranging it

Stopping and waiting

Any creative person you admire is probably doing some version of this.

When is copying wrong?

Above: The TV series Invasion (2023). Below: The Abyss (1989). Is this sort of copying wrong?

I’ve been watching the Apple TV+ series Invasion. There’s a scene in the show where I’m sure thousands of sci-fi fans all said, “Uh, that’s from The Abyss.”

You can see the two shots above. And yeah, they’re quite a bit alike. Is there anything wrong with this?

Let me talk this through using the example of the seventies hard rock band Led Zeppelin. (Click that link to watch this section of Everything is a Remix Part 1.)

There’s no doubt that Led Zeppelin were a highly imaginative group of musicians, especially Jimmy Page, the band’s guitarist and founder. Nonetheless, early in the band’s recording career, Page and Zeppelin repeatedly crossed an important line: the line between copying and plagiarism.

The clearest example of this is the song “Dazed and Confused.” Without a doubt, this was an uncredited cover of a song by Jakes Holmes. Check out the songs back to back in our playlist: Spotify, Apple Music. (They’re songs 31 and 32 in the list.)

Page plagiarized Holmes’ song.

So: copying is wrong when it’s plagiarism.

Uh huh. But when is copying plagiarism?

Copying is plagiarism when you copy too many parts at once.

For instance, Page could have copied a single part from “Dazed and Confused,” like its dark mood, the descending guitar line, a bit of the melody, even the title “Dazed And Confused,” which wasn’t Holmes’ invention.

But Page copied all these things. The Led Zeppelin version of the song does all of these things… and more.

(Yes, there’s plenty of original music and lyrics in the Led Zeppelin version, but as a whole, Zeppelin’s song is too much like Holmes.)

So what’s the verdict on this image?

In my opinion, it’s certainly not plagiarism. All that was really copied was a single element: reaching out to a gelatinous blob.

However, I will say this: I think these filmmakers could have done better. That moment from The Abyss is well-known and they could transform that idea more. This would make it less recognizable, and more importantly, make this scene more their own and more imaginative.

And that’s where we’ll head next, into the realm of transformation. This is how we take things we love and make them our own.

How AI Remixes the Human Imagination

AI is the new frontier of creative work. And remixing is deeply ingrained in generative AI software like ChatGPT and DALL-E.

All generative AI is trained on the infinite library of creative expression that is the internet. When AI “creates,” it is remixing. It copied loads of human work, then it transforms and combines this data to create new works.

The technology of AI itself is remixing human creative work.

But we also remix when we use AI.

When we write with AI, we can take our words and transform them into someone else’s style.

For instance, I can take the first paragraph of this post and have ChatGPT turn it into a children’s song. Here’s the first verse.

AI's a new frontier, so vast and bright,

A world where ideas take flight.

In the land of ChatGPT and DALL-E's art,

Creative journeys are about to start!

When we create images with AI, we cite styles and artists and remix them.

The image below was created by DALL-E using the prompt “create an image of the easter bunny rendered in a renaissance painting style.” To the right you can see its clearest influence, The Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci.

So how do you get started with AI creativity? Download our free toolkit, 11 Incredible Ways to Work With Al, to get started!

Originality Matters. But What Is It?

Bruce Willis in Pulp Fiction

Originality is a misleading concept. All new works, no matter how radical they seem, are derived from past works.

Like all young film nerds of the nineties, Pulp Fiction blew my frickin’ mind. The film was basically a long sequence of things I’d never seen before.

That Sam Jackson interrogation in the apartment

That sweet, awkward dance scene

A major character dying early (sure, I’d seen it a couple times – Psycho, To Live and Die in LA – but it was a rarity)

The gimp, the dungeon

The adrenaline shot

And most of all, the nonlinear structure

Pulp Fiction inspired many filmmakers, Guy Ritchie, Edgar Wright, and P.T. Anderson among them. And it influenced countless films, most noticeably with its nonlinear style, which was taken even further in the likes of Run Lola Run and Memento.

Love him or hate him, Tarantino is an original, to the point that he’s become his own genre.

And yet Tarantino is also derivative.

One of the later revelations that led to the idea of Everything is a Remix was my discovery of how Tarantino creates, which I would describe as steal liberally.

His first film, Reservoir Dogs, shared a lot of plot similarities with the Hong Kong action film, City on Fire (a far less notable film, by the way).

Tarantino’s later film, Kill Bill, was a brazen mash-up of dozens of martial arts films. I explored that in the original Remix series.

I later learned how Pulp Fiction was a stew of influences and some of the stand-out elements even had specific sources.

The Band of Outsiders dance scene is the inspiration for the one in Pulp Fiction

That sweet, odd dance scene had the same feel as the dance scene in Band of Outsiders.

One of the tensest scenes in the film, the adrenaline shot, was based on a moment from an early Martin Scorsese doc.

And that striking nonlinear style was a prominent element in loads of film noir, including Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing.

And yet, Pulp Fiction is original, Tarantino is original.

When something gets called “original” it simply means it seems original. It hit some sort of threshold where its novel qualities are far more striking than its familiar qualities. It doesn’t mean the work as a whole is without precedent.

Originality in that sense not only exists, it’s a vital quality of great creative work. Originality is one of the most enthralling and exciting features you can achieve. All the great filmmakers – Kubrick, Hitchcock, Bergman, Kurosawa, Spielberg, Lynch – are originals.

How does one achieve originality? I’ll explore that next time.

A Recipe for Awful Creative Feedback

Yields: 1 demoralized creative

Serves: None

A friend or colleague just sent you their book or film or app or product or album. They’ve worked very hard on it and would like your suggestions for improvement.

Naturally, you want to do the worst job possible and be as distracting as possible.

Follow this simple recipe!

Ingredients

100 tons of ego

Heaping tablespoons of vague suggestions

A pinch of resentment

Instructions

1. It’s about YOU

Look in the mirror and repeat this three times:

“I am what’s truly important.”

Smile, mouth only, no eyes. Crack your knuckles. Let’s get ready to rumble.

2. The truth hurts so make it HURT

Bluntly criticize and give opinions. Be cruel and careless. “This is boring!” “It’s just not working.”

NEVER give specific ideas for actions. NEVER express these notes in a neutral style.

Consistently insinuate that the work would be much better if it was done by you.

3. OVERWHELM and EXASPERATE

Inundate them with feedback, regardless of the project’s stage. Suggest major overhauls, preferably ones that contradict previous notes. Make it clear that scrapping the project entirely is the best overall choice.

4. Avoid BREVITY

Make your message as long as possible. Each point should be a winding essay with tangents. Let them luxuriate in your wisdom.

5. CAPS LOCK

Garnish your treatise with ALL CAPS.

6. KEEP SCORE

After you give your notes, be sure to KEEP SCORE. Which of your notes did they obey or disobey? If they didn’t do your note, that is a SLIGHT! Hold that grudge.

Casually bring up their “mistakes” at unexpected moments long after the project is complete.

Serving Suggestion: Ghost them for added confusion and despair.

Read Like an Artist

How Notes Fuel Your Creativity

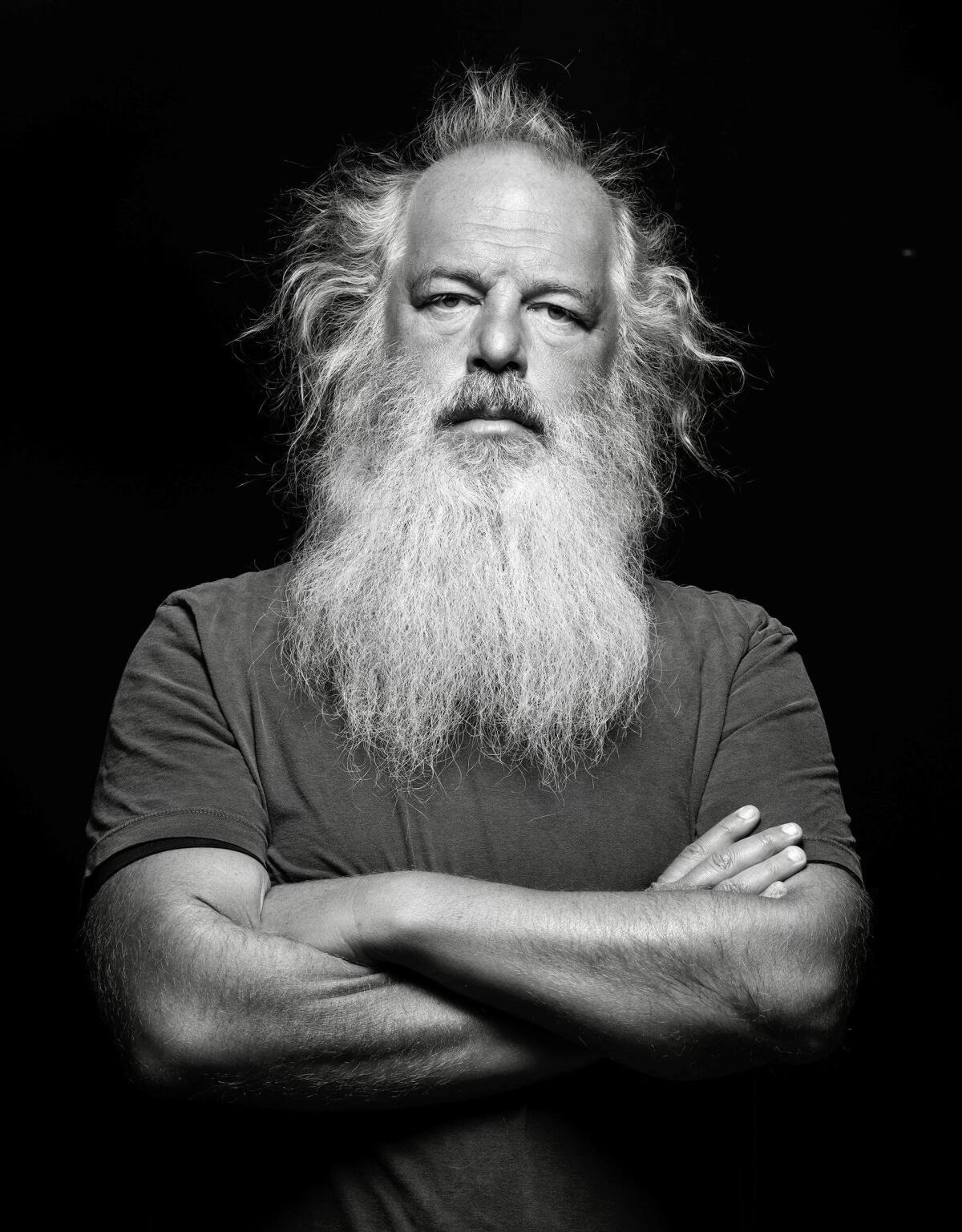

Rick Rubin

People don’t think of reading as creative. It’s considered passive, consumptive. Reading certainly can be those things, but it can also be highly creative if you do it the right way.

The simple key to creative reading is this: take notes. Make highlights and write notes. E-books are especially great for this and Readwise is the best tool to manage those notes. Your book highlights and notes should be part of a notes system that also includes your own notes drawn from your ideas, life, and experiences. Out of this brew of your thoughts and the thoughts of others, all sorts of ideas will appear.

Creating is so much harder if you don’t take notes. You’re perpetually stuck in the “blank page” phase, staring into the void and waiting for a lightning bolt of inspiration.

Another key to creative reading that I’ve discovered is this: timing is everything. Read the book when it’s time to read the book.

I pre-ordered Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act as soon as I saw it was coming and I was thrilled to see it pop up in my Kindle library later. Nonetheless, I didn’t dive in, I set it aside.

There are a special few books, movies, and albums that I save until it’s the right time to experience them. How do you know that moment has come? I dunno, it’s a feeling, but I think this feeling comes when the work fits within my current interests and might have a role to play.

The time for The Creative Act recently arrived and I’ve been slowly reading it over recent weeks. It’s an inspiring book regardless of how you read it, but saving it for this moment made it explosive for me. It’s inspired thousands of words of writing and many good creative insights.

The first thing it inspired came after reading this passage.

If you know what you want to do and you do it, that’s the work of a craftsman. If you begin with a question and use it to guide an adventure of discovery, that’s the work of the artist.

This idea combined with a recent conversation I had with my friend Andy Allen, then this article, “Art, Craft, and AI,” came flowing out. I think this piece is a strong insight, but it’s also an early expression and it’ll grow into something bigger and better

The Creative Act also inspired a new course idea. We’ll see what comes of that.

Because I read The Creative Act when it felt right (and made notes!), the book triggered countless ideas, many of which will continue to grow for months to come.

To read more articles like this, subscribe to my newsletter, The Midlife Remix.

Art, Craft, and AI

Guernica, by Pablo Picasso

The categories of art and craft need to be re-understood and perhaps even re-imagined for the age of AI.

Why? Because AI can do craft and it cannot do art. Let me explain.

What is art?

Perhaps you think of a painting hanging in a gallery. Maybe you think of a great artist like Frida Kahlo or Pablo Picasso.

This is a good foundation. Of course, art now comes in many forms, but the core purpose remains the same as it was for these artists. The purpose of art is to express something, to convey an emotion, a vision, or an idea. There is no practical purpose other than that.

Art is connection with another person. This expression is theirs alone and it cannot be duplicated without becoming worthless. Being Picasso mattered. Being like-Picasso didn’t.

What is craft?

Perhaps you think of woodworking, pottery, jewelry, knitting. That’s a good start too.

The craftsperson uses hard-earned technical skill to create something beautiful or useful. They also express something but this expression comes from their culture or heritage. It is not theirs alone.

Craft can also be created on screens or on paper. For instance, life drawing, portrait photography, and most web design are forms of craft. (There are exceptions of course and some people turn these into art.)

Craft is related to art, it’s also creative and it overlaps it, but it’s also very clearly different.

What’s the difference?

Many would say craft is more functional and practical than art, but I think the most important difference is this: the goal.

With craft, the goal is already explicit. You want a pleasing portrait of the wedding couple, with nice composition, nice poses and expressions from the couple, pleasing light, perfect exposure and focus.

With craft there is a formula and this formula can be converted into an algorithm. Here’s Midjourney’s version of a “gorgeous wedding portrait photo.” Infinite photos that look something like this have already been taken and will be taken for years to come. The formula for craft evolves over the years, but there is a formula. The fun and challenge of doing craft is to execute the formula as well as you can.

An AI-created wedding photo portrait

Art does not have a formula. It is ineffable, it is magical, it is shrouded in mystery. Art mostly happens in our subconscious mind and artists are famously inarticulate about how they do what they do.

Because there is no known formula, there is no algorithm.

Again, AI can do craft. It can’t do art. AI will surely improve at craft. It’s unclear if it will improve at art.

The artistic element of what you do will remain safe from automation, and it’s the most essential element of what you do.

How Irritation Turns Into Innovation

What do you think of when you think of a great invention?

I’ll guess it’s one of these.

The Internet

The personal computer

Something by Apple

The car

The airplane

The light bulb

What do all these have in common? Except for the light bulb, they’re traditionally considered man stuff.

But for sheer labor saved, what’s traditionally considered woman stuff ranks at the very top of all innovations. I’m talking about domestic appliances: the clothes washer and dryer, the vacuum cleaner, the modern stove, the refrigerator, and the dishwasher. The story of the dishwasher is especially inspiring… although it doesn’t begin that way.

This story starts with a rich lady being fed up with her clumsy house staff.

Josephine Cochrane, inventor of the dishwasher

In the 1880s, Josephine Cochrane, a wealthy Illinois socialite, was irritated by her servant's repeated chipping of her fine china. Not exactly the makings of a feel-good biopic here.

But Cochrane still fits the bill for our romantic vision of the inventor. Soon after she conceived her idea, Cochrane’s husband died. She needed to make a living and she was an outsider. Cochrane was a woman in the 19th century and not an engineer or mechanic.

Nonetheless, she knew what she wanted: a machine that would wash dishes without scrubbing. She pieced together a primitive prototype in her back shed, with the assistance of a mechanic.

Cochrane’s resulting machine could wash dishes faster and more safely than manual washing. Her design of racks to hold the dishes and water jets to clean them remains the foundation of modern dishwashers.

How much time has the dishwasher saved us? Most families will save about 40 minutes per day using a dishwasher. In a year, that’s about 6 weeks of full-time work.

I’ve lived most years of my adult life without a dishwasher. I’ll say this: life is a little bit better with one. Consider this a testament to how irritation turned into innovation by a determined woman in the 19th century.

AI and The Shock of the New

Nick Cave screams into the void

“The Shock of the New” is culture’s allergic reaction to new art forms. It’s an attempt to kill off the invader.

Whether it’s hip hop or comic books or the blues or video games, or movies or TV or fan art or even novels, these were all considered “not art.” They were lower, inferior, and contemptible forms, not capable of conveying the insight, humanity, and emotional breadth of real art.

This doesn’t just happen with art, it happened with the internet, cars, trains, factories, or electric lights. Anything that was once new – which is everything – was subjected to the shock of the new and targeted for defeat or elimination.

This is happening now with AI.

These attacks come from many different angles, but I want to focus on my domain: creativity and art.

In this realm, the singer-songwriter Nick Cave has been one of the most persuasive and eloquent critics of AI as a creative tool. Cave wrote an influential and ferociously critical letter about ChatGPT. Cave’s words have resonated widely in the months since he wrote it. (If you don’t like reading, you can watch Stephen Fry read the letter here.)

Cave argues that writing song lyrics with ChatGPT is “participating in [the] erosion of the world’s soul and the spirit of humanity itself.”

Holy shit guys!

Nick Cave certainly has wisdom to share about the value of art and how it enriches your life. But he doesn’t have wisdom about ChatGPT, and c’mon, has he ever used this stuff? Judging by his level of revulsion, which is extreme, I’d guess he’s probably never typed a single prompt.

I’m not a great artist like Nick Cave, but I am artistic and I have used ChatGPT for creative tasks. Anybody who has done the same knows this: ChatGPT is bad at art.

If you want bad lyrics, ChatGPT can write those. And y’know, for most pop music, bad lyrics are good enough, so let’s start there.

Yeah, you got that yummy, yum, That yummy, yum, That yummy, yummy

Bad lyrics are good enough

Cave thinks songwriting with the assistance of ChatGPT is not songwriting. Here’s a bit from his letter where he addresses a songwriter who uses ChatGPT for lyrics because it’s quicker and easier.

That ‘songwriter‘ you were talking to … should fucking desist if he wants to continue calling himself a songwriter.

Cave thinks the lyrics of songs are of paramount importance. But lots of musicians and fans do not share this opinion.

Cave makes serious music with serious lyrics. But most people don’t wanna hear that shit. Of all the millions of songs being streamed right now, almost all of that music has stupid lyrics.

Here’s some of Justin Bieber’s famously stupid “Yummy.”

Yeah, you got that yummy, yum

That yummy, yum

That yummy, yummy

It goes on like that.

That song has 770 million views on one platform. It certainly has over a billion listens in total.

Pop music is mostly stupid. You and I and Nick Cave might not like that kind of music, but most people do. They want catchy songs they can sing along with and the lyrics are often unimportant.

If pop artists want to quickly write stupid lyrics with ChatGPT rather than dash them off themselves, I’m sure we’ll all be fine.

But stupid lyrics aren’t just for stupid artists. Lots of great musicians don’t care much about lyrics and toss them together at the last moment.

Mumble mumble mumble

Good music has stupid lyrics too

Plenty of great artists don’t necessarily value lyrics and sang meaningless strings of words.

David Bowie sometimes wrote jibberish lyrics. “Life on Mars” sure is a great song, right? Ever listened to the lyrics? No, you haven’t, but here’s a bit of what’s actually said.

It’s on America’s tortured brow

That Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow

Now the workers have struck for fame

’Cause Lennon’s on sale again

Michael Stipe’s early lyrics with REM were entirely jibberish and maybe not even words at all. Here’s a bit of “Radio Free Europe” (whatever that means).

Keep me out of country and the word

Deal the porch is leading us absurd

Push that, push that, push that to the hull

That this isn’t nothing at all

Plenty of Nirvana’s lyrics were written by Kurt Cobain moments before recording. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” starts like this.

Load up on guns, bring your friends

It’s fun to lose and to pretend

She’s over-bored and self-assured

Oh no, I know a dirty word

Again, bet you never knew most of what was being said there.

Cave would certainly not dismiss David Bowie, Michael Stipe, and Kurt Cobain as “not songwriters” and yet they tossed together lyrics like they were scribbling homework minutes before class.

The most important part of music is, y’know, the music. And inane or banal lyrics can be compelling in the right musical context.

Is prompting ChatGPT less creative than stringing together rhyming syllables? Perhaps it is if you just cut and paste ChatGPT responses, but I’m gonna argue that many songwriters probably won’t be doing that.

William Burrough’s famous novel Naked Lunch was sliced together from existing texts

ChatGPT is useful for good art

One of Cave’s major themes is that ChatGPT undermines artistic struggle.

ChatGPT rejects any notions of creative struggle, that our endeavours animate and nurture our lives giving them depth and meaning. It rejects that there is a collective, essential and unconscious human spirit underpinning our existence, connecting us all through our mutual striving.

I suspect Cave is imagining someone prompting ChatGPT for lyrics, cutting and pasting whatever it spits out and presto.

This is not the reality of creating something good with ChatGPT. This entails lots of editing, rewriting, and writing. ChatGPT is a powerful tool, but it is extremely dependent on the orchestration of a living person, with a heart and a soul. The creative struggle is still very much real if you want to write good lyrics.

The best ChatGPT can do is create fragments that a creative person can isolate, then copy, transform, and combine those bits and others into something good.

There is, of course, a rich history of artists thinking like this.

The writer William Burroughs popularized “The Cut-up Technique” in the sixties. He used to cut out bits of text and string ’em together. Bowie, Cobain and Thom Yorke all did the same thing for lyrics.

I made a documentary series about how this technique applies not only to words, but to music, film, technology, science, and ideas. Everything is a Remix, folks.

Music listeners aren’t idiots

One of the weaknesses of the artistic mindset can be insularity. Put more bluntly: your head is stuck up your ass. Sitting by yourself and composing your great thoughts often means you’re pretty into yourself. I’m speaking from experience here.

Cave is guilty of this in his letter. He’s thinking of his own struggle and striving, but he’s not thinking of his partner in the dance, the listener.

I’ve spent thousands of hours of my life as a listener. The listener is seeking connection with another soul and insight into themselves and into life.

Only extraordinary experiences can do this. If good art is easy and common, then good art is worthless. If everybody can spit out great lyrics with ChatGPT, nobody will be paying attention. The truly great work will have to be even better – or at least different.

Great art gets attention because it is extraordinary. This doesn’t mean it’s better, it just has something unusual. If ChatGPT starts writing good lyrics, the differentiator for good lyrics will move elsewhere, and great artists will still struggle to create this extraordinary work.

There just has to be an apocalypse

Steeped in Biblical narratives as he is, Cave’s vision just has to culminate in a Book of Revelation-style apocalypse. He can’t just say that ChatGPT sucks and you suck if you use it.

ChatGPT has to be “[eroding] the world’s soul and the spirit of humanity itself” and “just as we would fight any existential evil, we should fight it tooth and nail, for we are fighting for the very soul of the world.”

Holy shit Part Two!

Here’s my guess about what’s coming: culture is more resilient than people think. We’ll all adapt, the shock of the new will fade away, and life just goes on. The whole panic gets forgotten and then gets repeated for The Next New Thing.

Art created with AI is not yet good. But it will be. And it won’t happen because AI is that much better, it’ll be because brilliant people find a way.

Age of Deceleration

Part 2 of "Are We Creatively Losing It?

This computer is 10 years old

In my last installment, I asked this question: are we creatively losing it? Go read that before reading on.

The most obvious counter to this question is: but technology!

Yes, there is that. For example.

AI, above all, is exploding.

Augmented reality might be about to go mainstream with Apple’s Vision Pro.

Even the widely despised crypto/web3 is vital, has exciting potential, and is currently worth a fortune. The real question is whether it can do anything or not.

Tech remains an innovative and dynamic realm… but it is definitely slowing down too.

Think about this.

It’s 2024. Let’s say you’re using a ten-year-old computer that you bought in 2014.

It’s a bit sluggish, it can’t run the latest operating system, but it does everything you need. It even pretty much looks like the new models. Sure, you want a new computer, but you’re fine.

Now hop in a time machine and set the dial for 2004.

A new iMac in 2004 looked like this.

But you’re not using that. Again, you’re using a ten-year-old computer. It’s 2004 but your computer is from 1994. That’s something like this.

This beast is an ancient relic. It’s a gray box with a huge, heavy monitor. It’s unbearably slow and has no storage space. You store your extra files on, yep, a stack of floppy disks.

You are miserable and desperate for an upgrade. You’re not fine.

Computer hardware was a runaway train in the eighties and nineties. But not anymore.

You can feel this. You can feel each new iPhone or new laptop being a smaller and smaller upgrade. More likely, you’re upgrading because the old thing is broken.

Tech is still briskly advancing and some areas, like AI, are explosive. But it is slowing down. Those of us who experienced the break-neck innovations of the eighties and nineties have witnessed this deceleration.

But the slowdown in tech is minor compared to the slowdown elsewhere in society. Next time up I’ll show you just how slow progress has gotten in the rest of human creativity.